|

Versione italiana |

Most people have a clear understanding of what the term ‘family farm’ means1. This is especially true in Europe. The term refers, in a seemingly straightforward and unambiguous, way to well-known and self-evident realities. It is solidly internalized in the memory of most people, even those with an urban background. People may like or dislike family farming and scientists may dispute its virtues or shortcomings. But there seemingly is any confusion or debate over the concept itself.

However, these certainties become less-evident when the context in which family farms are embedded changes drastically and this can lead to a rethinking, questioning or even contestation of the concept. This happened after World War 2 when agriculture experienced a massive restructuring. At that time Folke Dovring, an experienced staff member of the Fao in Rome, observed that “the family farm especially is obscure in definition” (1956:99). The same occurs when the family farm itself experiences deep and far reaching alterations.

The uniqueness of our times is that both context and the family farm itself are going through drastic transitions. The, once stable, reality of the family farm is being radically affected – both from the outside and the inside and this requires, probably more than ever before, a rethinking of the concept.

This paper addresses a basic and seemingly simple question. What does the family farm mean for the actors involved in it? Related to this is another question: why, how and under what conditions is family farming important to society as a whole?

Within Europe family farming is the dominant, although not exclusive, land-labour institution2. This has not always been the case, and it is not a foregone conclusion that it will continue to be the case. In recent history (1850-2000), Europe had an important sub-sector of capitalist farm enterprises. Some pockets apart (notably Scotland, Andalucia, the Italian Mezzogiorno and parts of Eastern Europe) this sub-sector was strongly reduced, mainly due to the devastating agrarian crises of the 1880s and the 1930s as well as to land reform processes that took place, particularly in northern and central Italy in the immediate aftermath of WW2 and in Portugal after the Carnation Revolution of 1974. Eastern Europe witnessed a re-emergence of family farming (alongside a rise of large, capitalist farms) after de-collectivization.

Nowadays, out of a total of 12,248,000 farms in Europe (EU28), some 11,885,000 (i.e. 97%) are classified as family farms. In the remaining European countries one encounters more or less the same situation. The notable exception is Russia where family farming and corporate agriculture co-exist. In Russia and Western Cis countries family farms only cover 34% of all land (although they produce 62% of all output).

It would be imprudent, though, to hypothesize that this dominant position of family farms represents a stable situation. Firstly there is a ‘growth-pole’ of rapidly expanding farms within the family farming sector. This is not only leading to an accentuated concentration of land (and other resources), it also gives rise to farm enterprises that are partly built on wage-labour (often in disguised form)3. Within the EU27 the larger farms4, which on average have an Utilised Agricultural Area (Uaa) of over 1,000 ha, represent only 0.6% of the total number of farms. Nonetheless, they cover 20% of all Uaa in Europe (a total of 35 million ha., which equals the total area of Germany) (Eurostat 2011:2-3). These newly emerging ‘mega-farms’ are having a significant impact on the rest of the family farming sector.

Secondly, on the ‘borders’ of Europe one sees the construction of, often extremely large, capitalist farms (mostly with a network structure) that can now– due to deregulation and liberalization - directly commercialize their products on European markets. Once such large farm enterprises were very ‘far away’, now their presence and produce represent an undeniable reality within European markets: they directly compete with produce from family farms located in Europe. For example Van Oers United BV is a horticultural enterprise that operates in Portugal, Morocco, Senegal and Ethiopia and has 1,300 hectares of irrigated land in Morocco alone. For horticulture that is unprecedented. Equally there is a dairy farm in Russia (Ekosem Agrar) that has 18,000 head of cattle and is expanding to 36,000 heads. On the Eurasian continent this is unprecedented. In Romania there is an arable farm of 12,000 hectares which only has 10 employed workers (Emiliana West Rom). Once again: unprecedented. These newly constructed corporate farms (there are hundreds) may very well flood the main European markets with cheap commodities, negatively affecting the existing family farm sectors. The European Commission organized an extensive e-consultation in the run up to the International Year of Family Farming (2014) which showed that ”competition with large scale corporate farming” is seen as the second largest ”key economic challenge for family farms”. The largest key economic challenge was “bargaining power within the value chain” (2013:33). This is also related, albeit less directly, to the presence of corporate agricultural enterprises. Their (real or potential) supply evidently weakens the position of family farms vis-a-vis food industries and large retail chains.

Thirdly, it should be recognised that in some sectors, in some areas, farmers are so indebted that they hardly actually own the family farm anymore. Most of the value of the farm is owned by the banks. This is an issue for many large and modern horticultural enterprises in the Netherlands that de facto belong to the Rabo bank. The same applies to many wine producing farms in Italy that are virtually owned by the Monte dei Paschi di Siena bank. If these banks decide to sell these farms (in case of default), it is possible that large scale, corporate farm enterprises could also emerge in the heart of Europe.

In short: the relations between family farms and corporate farm enterprises are being redefined, both within and beyond national and supranational borders – this is a contradiction of a truly global dimension. The presence and apparent dominance of the family farm in Europe and Central Asia is far from guaranteed and the current situation could well abruptly change.

A wider range of features

In contemporary Europe, nearly everybody agrees about the standard definition of the family farm. It is, in the first place, a farm in which most of the resources required (land, buildings, crops, animals, machinery, knowledge, networks, etc.) are controlled by the farming family. Secondly, most - if not all - of the work is done by family members5. The advantage of this definition is that it is easy applicable (i.e. it can be operationalized in statistical terms) and mostly uncontested (although borderline cases may provoke considerable debate). The two features also figure in the definition used by Fao: “A family farm is an agricultural holding which is managed and operated by a household and where farm labour is largely supplied by that household”. At the same time, though, this definition sometimes turns out to be problematic, partly due to its simplistic nature. It takes just two characteristics out of a much wider set of features that together constitute family farming.

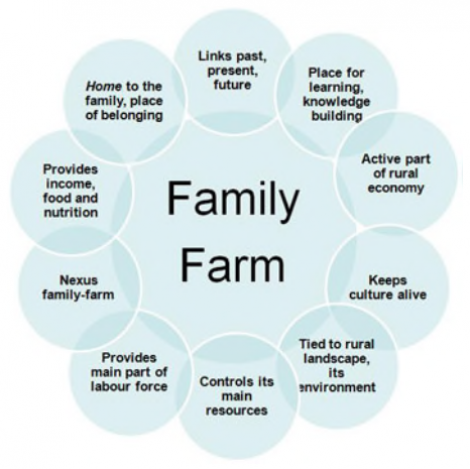

This wider range of features (see also Gasson and Errington, 1993) is described below and illustrated in figure 1. In practice, these features provide the (potential) qualities of family farming. Individually, but especially when taken together, they constitute the attractiveness of the family farm and they contribute decisively to its relevance for society. Not all of these features are always present: this depends on time and place. The family farm may unfold completely (then all qualities are strongly present). It may, however, as well suffer from processes of erosion (then only a few features remain).

Figure 1 - The multiple features of the family farm

Derived from Ploeg 2013

-

Autonomy. A first defining feature of the family farm is that the farming family retains control over the main resources used in the farm. This control is often (but not necessarily) rooted in property rights. The resource base includes the land, together with the animals, the crops, the genetic material, the house, buildings, machinery, labour force and, in a more general sense, the know-how that specifies how these resources need to be utilised and combined. Access to networks and markets, as well as co-ownership of co-operatives, are also important resources. Many of these resources have been constructed and/or acquired through long processes covering different generations. These resources are often the result of hard work, dedication and the hope for a better future. Family farmers use these resources, not to make a profit, but to make a living; to acquire an income that provides them with a decent life and, if possible, allows them to make investments that will further develop the farm.

The ownership and control of these resources provide the farming family with an important degree of (relative) autonomy. It allows them to face difficult times as well as to construct, with their own work, attractive prospects for the future. In this respect, their control over the resource base indeed is a quality, the importance of which is reflected in the value of being independent (of ’being one’s own boss’). Autonomy is especially valued because it gives the primary producers control over the labour process, allowing them to mould agricultural production in a way that optimally corresponds with their needs and strategies (thus giving rise to different styles of farming).

At the same time the level of autonomy that farmers have over their resource base is far from self-evident. In reality it is being eroded in many places. High degrees of indebtedness and increasing financialization imply that the real control shifts to banks and/or processing industries. Strict regulatory regimes imposed by state apparatuses and/or processing industries also reduce farmers’ control over their resource base -

Self-employment. A second defining feature relates to the farming family providing the main part of the labour force. This makes the farm into a place of self-employment and of progress for the family. It is through their dedication, passion and work that the farm is further developed and the family’s livelihood is improved. The farm is there to meet the many needs of the family, whilst the family provides the possibilities, the means and also the limitations for the farm. This feature often emerges as a quality. For the family members working on the family farm work frequently involves an attractive set of highly diversified activities. It is work with living nature, often in the open air, and it is possible for them to avoid a rigid organization of their working days. The work is also attractive because it builds on an organic unity of mental and manual labour. Available surveys show that all those who work on family farm appreciate these aspects of their work. However, all is not unbridled attractiveness and satisfaction. In practice family farming always implies a balance of drudgery and satisfaction. The important fact, however, is that – at least in the ideal situation – it is the involved actors themselves who determine, often in a coordinated way, these balances. Equally important, farmers are ingenious at finding novel ways to reduce the drudgery as much as possible.

There is a mirror-side to this. Intra-generational and/or gender relations may induce sharp imbalances, and lead to a highly unequal distribution of drudgery and satisfaction, often resulting in satisfaction for a few (notably the male heads of the family, the padri padroni) and drudgery for the others (notably women and youngsters). Very low levels of remuneration and long working days are modern forms of drudgery. Recent research in Italy indicates that many young people who have an interest in farming, actually refrain from it due to this new form of externally-induced hardship (Rete Rurale, 2013). -

Co-evolution. The nexus between the family and the farm implies a third defining feature. The major decisions about the organization and development of the farm are taken within the farming family itself. The family’s interests and prospects are at the core of the many decisions that are to be taken. Decision-making involves making balances, such as those discussed above, as well as others, such as that between the ‘supply’ of family labour and the organization of the farm. Another important balance regards the social organization of time: short term actions need to be well-coordinated with long term prospects. Balances like these tie family and farm together. The two co-evolve simultaneously. Through this co-evolution each defines and moulds the other. But again: the unity of family and farm can very well become disarrayed or disrupted. This might occur when prolonged days of hard labour and heavy work, combined with low levels of remuneration create a seemingly hopeless, endless, and inescapable routine. At this point family farming turns into (voluntary) enslavement. As with the other features, co-evolution also can have a bright, as well as a dark, side. That makes family farming an ambiguous concept. It can bring emancipation and development, but it can equally bring stagnation and misery. This balance is highly dependent on time and place. Family farming is not immune from history, geography or society. It is integrally linked to them and societal conditions strongly influence which of Janus’s faces will be visible.

-

Creating wealth. There is far more in the family farm than ownership, labour and decision making. A fourth defining feature is that family farms provide the farming family with a part (or all) of its income and food. Having control over the quality of self-produced food (and being confident that it is not contaminated) is becoming increasingly important for farmers around the world. Family farms have the capacity to produce more, with a given set of resources, than other forms of production (e.g. corporate farms). In comparative analyses family farms emerge as achieving the highest yields (i.e. the highest levels of physical productivity). In addition, family farms are able to realize, at a given level of total production, the highest incomes. These distinguishing features imply that family farms are able to maximize (far more than other forms of production) the value added from primary production. They do so because obtaining a good family income (and securing the long term prospects of the farm) is their prime objective. This search for income translates into intensity levels (yield per hectare, production per animal, etc.) that are generally superior to those realized in corporate farms.

In Europe the majority of family farms have members who are also engaged in off-farm economic activities. This phenomenon is mostly referred to as pluriactivity but also known as multiple job-holding or as part-time farming. In Dutch agriculture, for instance, 80% of all farming families have the man or woman earning an additional income outside of the farm. This additional income contributes on average 35% to the total family income. Italian agriculture in 2010 generated 26 billion Euro, but pluriactivity added another 18 billion Euro. There may be many reasons for engaging in pluriactivity and they can be contradictory. Pluriactivity may represent a form of risk aversion. Farmers do not like to have ’all their eggs in one basket’. It might represent an attractive alternative to daily routines (this is often the case for rural women) or it may provide the capital needed to invest in enlarging and/or improving the farm (this is often the case for young farmers). But pluriactivity might also be needed to complement the family income because farming itself provides an inadequate income. In this case pluriactivity is experienced as coercion, an unavoidable, rather than enviable, destiny. However, it is also experienced, at least by some, as an opportunity to employ one’s own talents and skills outside of the farm and extend their social contacts. Pluriactivity has the potential to combine the best of two different worlds (the rural and the urban). Be this as it may, pluriactivity enables many farming families to sustain their incomes and also make a contribution to supporting and developing regional rural economy.

A relatively new development occurring throughout Europe is that family farmers increasingly develop new economic activities within the farm in addition to conventional farming. This is mostly referred to as multifunctionality. One interesting finding is that such new, multifunctional, activities contribute to sustaining food production itself (de Rooij et al, 2014). -

Domus. The family farm is not only a place of production. It is also home to the farming family. It is, indeed, domus as the ancient Latin expression goes (Le Roy Ladurie, 1975). It is not only the place that gives people shelter but also the place people belong to. It is where the family lives and where their children grow up. Recent Italian research shows domus to still (or again?) be a major factor that explains the vitality and resilience of family farming and thus the continuity of food production (Rete Rurale, 2013). Domus makes farming into a livelihood: it introduces strong links between cultural repertoire and agricultural practices. The relative weight of domus and agriculture will vary considerably. Nonetheless, domus is strategic in family farming.

-

A flow through time. The farming family is part of a flow that links past, present and future. This means that every farm has a history and is full of memories. It also means that the parents are working for their children. They want to give the next generation a solid starting point whether within, or outside, agriculture. And since the farm is the outcome of the work and dedication of this, and previous, generations, there is often pride. There can also be anger if others try to damage or even destroy the jointly constructed farm. ‘Keeping the family name on the land’ has been important throughout agrarian history (see Arensberg and Kimball, 1940) and helps to explain at least a part of farmers’ resilience these days to outside pressures.

-

A place for learning. The family farm is the place where experience is accumulated, where learning takes place and knowledge is passed on to the next generation. The family farm is a node in wider networks in which new insights, practices, seeds, etc., circulate. Thus, the farm becomes a place that produces agricultural know-how which is combined with innovativeness (Osti, 1991) and novelty production (Wiskerke et al., 2004). In a classical contribution to the literature Giampietro and Pimentel (1993) refer to the “dual nature of agriculture”: it provides society’s needs and deals with the natural ecosystem and must ensure compatibility between the two (see also Toledo, 1990). Agriculture depends on, uses and transforms the ecosystem and the associated natural resources. Due to the highly heterogeneous nature of ecosystems and constant changes in them over time (both short and long term), the interactions between family farmers and their fields, animals, crops and the climate, require ongoing cycles of observation, interpretation, intervention and evaluation. In other words, human agency is central in family farming and with it comes the strategic importance of skills, practical knowledge (or: art de la localité as Mendras 1987 beautifully phrases it) and ongoing learning.

-

A carrier of culture. The family farm is not just an economic enterprise that focuses mainly, or only, on profits, but a place where continuity and culture are important. The farming family is part of a wider rural community, and sometimes part of networks that extend into cities. As such, the family farm is a place where culture is generated, kept alive and transmitted to others and to future generations. Many farms are places of cultural heritage. As the Regional Conference on Family Farming (2014:5;23) observed: “Family farmers [....] preserve traditional cultures. The existence of family farms, particularly small-scale ones, is a significant part of national cultural heritage, customs, dress, music, cuisine and habitats”.

-

A cornerstone of the rural economy. The family and the farm are part of the wider rural economy, they are tied to the locality, carrying the cultural codes of the local community. Thus, family farms can strengthen the local rural economy through what they buy and spend their money on and by engaging in other activities. The strategic role of family farming for the regional rural economy is one of the major components of the ‘European Model of Agriculture’, endorsed by the European Council in 1997. It aims at “a farming sector that serves rural communities, reflecting their rich tradition and diversity, and whose role is not only to produce food but also to guarantee the survival of the countryside as a place to live and work, and as an environment in itself” (European Commission, 2004). We can find specific examples of this: the mezzadri in Italy who transferred their networking capacities into the towns, and gave rise to a blossoming Sme sector (Bagnasco, 1988) and part-time farmers in Norway who, having a strong fall-back position, were largely responsible for the introduction of strong labour unions and democratic relations in Norwegian society (Brox, 2006).

-

Building on nature and a part of the landscape. The family farm is equally part of a wider rural landscape. The family farmer may work with, rather than against nature, using ecological processes and balances instead of disrupting them, thus preserving the beauty and integrity of landscapes. When family farmers do this, they also contribute to conserving biodiversity and to fighting global warming. The work implies an ongoing interaction with living nature – a feature that is highly valued by the actors themselves. This quality is increasingly being recognized and supported by the Second Pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union.

The features described above illustrate the strength of the family farm as a major land-labour institution. From an economical point of view the search for autonomy (1), self-employment (2) and the farm being a place for learning (7) systematically translate into a lowering of monetary costs and an increase in technical efficiency. This latter aspect implies that the function of production is moved upwards. When it comes to food security the combination of co-evolution (3), the creation of value added (4) and the flow linking past, present and future (6) translate into continuity, robustness and resilient food production. And being a cornerstone of the rural economy (9), a carrier of culture (8), a co-shaper of landscapes (10) and domus (5) strongly support the quality of life in rural areas just as they strengthen the regional rural economy.

If, however, these features are weakened (that is, if family farming is eroding), production and both land and labour productivity will go down; food security will come under considerable threat; food provisioning will become more expensive; and the strength of the regional rural economy and the quality of rural society will decrease – possibly irreversibly.

References

-

Arensberg C.M. and S.T. Kimball (1940), Family and Community in Ireland, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass

-

Bagnasco A. (1988), La Costruzione Sociale del Mercato, studi sullo sviluppo di piccole imprese in Italia, Il Mulino, Bologna, Italy

-

Brox O. (2006), The Political Economy of Rural Development: Modernisation without centralisation? (edited and introduced by J. Bryden and R. Storey), Eburon, Delft

-

Chatel B. (2014), Collective challenges, in: Spore Special Issue (2014), Family Farming: the beginning of a renaissance, Cta, pp. 4-7

-

Djurfeldt G. (1996), ‘Defining and operationalizing family farming from a sociological perspective’, in: Sociologia Ruralis, Vol 36, no 3., pp340-351

-

Dovring F. (1956), Land and Labor in Europe 1900-1950, a comparative survey of recent agrarian history, Martinus Nijhoff, the Hague

-

European Commission (2004), What is the European Model of Agriculture? [link]

-

European Commission (2013), Summary of Proceedings, Conference on Family Farming: A dialogue towards more sustainable and resilient farming in Europe and the world, 29 November 2012

-

Eurostat (2011), Statistics in Focus, 18/2011, European Commission, Brussels

-

Gasson R., G. Crow, A. Errington, J. Hutson, T. Marsden and D. M. Winter (1988), The farm as a family business: a review, in: Journal of Agricultural Economics Volume 39, Issue 1, p 1-41 [link]

-

Gasson R. and A. Errington (1993), The Farm Family Business, Cab International, Wallingford

-

Giampietro M. and D. Pimentel (1993), The tightening conflict: population, energy use, and the ecology of agriculture, on: [link]

-

Le Roy Ladurie E. (1975), Montaillou, Village Occitan de 1294 á 1324, Gallimard, Paris

-

Mendras H. (1987), La Fin des Paysans, suivi d’une reflexion sur la fin des pasans: vingt ans aprés, Actes Sud, Hubert Nyssen, Editeur, Paris

-

Osti G. (1991) Gli innovatori della periferia, la figura sociale dell’innovatore nell’agricoltura di montagna, Reverdito Edizioni, Torino, Italy

-

Pearse A. (1975), The Latin American Peasant, Frank Cass, London

-

Ploeg J.D. van der (2013), ‘Ten qualities of family farming’, in: Farming Matters, Vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 8-11

-

Regional Dialogue (2014), Outcome of the Regional Dialogue on Family Farming, Brussels, 11-12 December 2013

-

Rete Rurale (2013), Il Part-time in Agricoltura: Caratteristiche ed importanza del fenomeno per lo sviluppo delle aree rurali Italiane, Ministero delle Politiche Agricole, Alimentari e Forestali, Roma

-

Rooij S. J. G. de, F. Ventura, P. Milone and J. D. van der Ploeg (2014), Sustaining food production through multifunctionality: the dynamics of large farms in Italy, in: Sociologia Ruralis, Vol. 54, Number 3, pp. 303-320

-

Toledo V. M. (1990), ‘The ecological rationality of peasant production’, in M. Altieri and S. Hecht (eds.), Agroecology and Small Farm Development, Crc Press. Place, page numbers?

-

Wiskerke J. S. C. and Ploeg, J. D. van der (2004) Seeds of Transition: Essays on novelty production, niches and regimes in agriculture, Royal van Gorcum, Assen, the Netherlands

- 1. This text is an abbreviated version of a document I prepared on the request of the Fao on the occasion of the International Year of Family Farming.

- 2. A land-labour institution is “the framework within which the individual producer’s decisions are made, and the medium through which the press and flow of events and process on a societal and world scale become real forces affecting his [or her] life and livelihood” (Pearse, 1974:1). It is an institution that ties land and labour together into a specific whole that puts its imprint on both land and labour. There are many different land-labour institutions, many of which have been very well-documented. The family farm is a unique land-labour institution in that labour and control systematically coincide: the direct producers are the owners of the most important resources used in the process of production. This implies that the family farm and productive activities located in it may become a vehicle for emancipation.

- 3. Many aspects of the labour process are sub-contracted to external firms that deliver ‘services’. Thus, from a formal point of view there are very few wage labourers within the farm.

- 4. In its definition of ‘larger farms’ Eurostat takes into account the specific distribution of land in each Member State.

- 5. Gasson et al. propose a slightly different definition based around three features: a) the principals are related by kinship or marriage; b) business ownership is usually combined with managerial control; and c) control is passed from one generation to another within the same family (1988:2). However, this particular definition omits the labour dimension. As observed by Djurfeldt (1996), this definition carries a UK bias.